The first Filipino known to visit Alaska came in 1788, aboard a Spanish trading ship called the Iphigenia Nubiana. The ship passed by Kodiak Island, where Russia had founded one of its first permanent settlements in Alaska a few years earlier.

That’s according to research by Thelma Buchholdt, the founder of the Filipino Heritage Council of Alaska and the first female Filipino American legislator in Alaska and the U.S.

According to Buchholdt, that sailor’s name was lost to time. He’s listed in the captain’s journals only as “Manilla man.”

Ship records note a handful of “Manilla men” coming to trade with Alaska Natives before the 1800s. At least 27 more came on whaling ships through the 1800s.

The Alaskeros establish the first organized communities

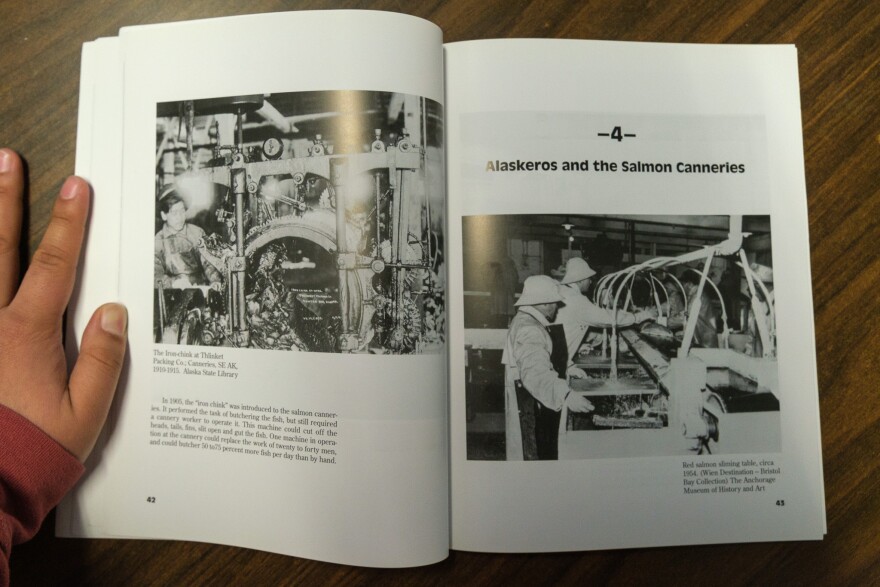

The U.S. bought Alaska in 1867, and the first big waves of Filipinos to make the territory their home came late in the century, when the salmon business went industrial.

“They were coming for education, they wanted to follow the American dream,” said Katherine Ringsmuth, Alaska’s state historian.

In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, cutting off a source of cheap labor. In 1898, Filipinos became U.S. nationals when the United States annexed the Philippines as a colony after the Philippine-American War.

By then, Ringsmuth said pre-Exclusion Act Chinese migrants were aging out of the workforce. That set the stage for American companies to hire Filipino people.

“So the Filipinos, who could speak English, who understood American ways of doing things, fit right in there perfectly and really began to dominate the cannery workforce right up through the 21st century,” she said.

In the early days of the territory’s commercial fisheries, one of the first groups to organize were the Alaskeros, or Filipino salmon cannery workers

“Filipinos would be the ones to really lead the way in organizing labor and unionizing,” Ringsmuth said.

Even though they were seasonal workers, the unions fought for better food, working conditions, and more equitable hiring practices. The Filipino cannery workers later sued to end segregation in cannery bunkhouses.

“This kind of racialized segregation of the canneries – is it constitutional?” Ringsmuth said “And they end up winning that case.”

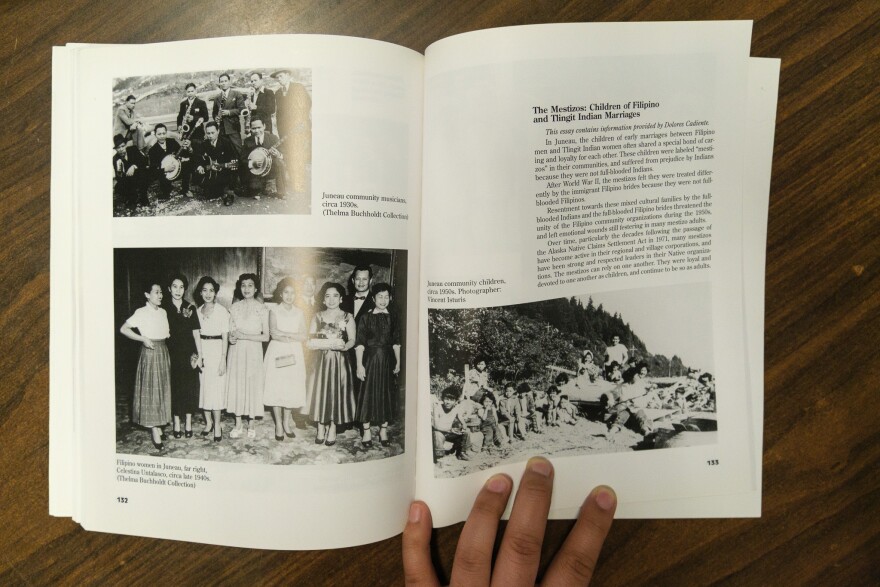

Canneries used to separate workers by country of origin but switched to numbers after the union won its lawsuit. The legacy of the Alaskeros set the foundations of organized Filipino communities in Alaska – now the state's largest group of Asian Americans.

The number of new Alaskeros cannery workers wound down after Congress further curbed immigration from Asia with new restrictions in 1924. Still, the Filipino diaspora reaches everywhere across the state.

The Kodiak Island Borough has some of the highest concentrations – about a quarter of the population has some kind of Filipino heritage. Anchorage has a population of 18,000 Filipino people, with thousands more across the state totaling to around 35,000 people.

World War II created a new labor shortage

“During World War II, the United States asked for assistance with the Filipinos to help them,” said Gabriel Garcia, a professor at the University of Alaska Anchorage. He’s teaching a course on Filipino history and community, which starts in the fall.

Under the Second War Powers Act of 1942, military service gave U.S. nationals, who can’t vote or run for office, a path to citizenship.

“That was one of the perks that was promised to the Filipinos at that point,” Garcia said. “And so many Filipinos from all over the Philippines enlisted as members of the military here in the U.S.”

After WWII, the Philippines received its independence, becoming its own nation in 1945.

Immigration after Independence

Filipino immigration boomed again about 20 years after that, when the federal government lifted immigration restrictions from Asia.

“The ban was lifted in 1965, so post-1965, that’s when immigration numbers again significantly increases, specifically in the Filipino community,” Garcia said.

Many of these new immigrants were engineers, doctors, educators, and other professionals. Filipino nurses in particular immigrated in droves through the Exchange Visitor Program.

Schools there primarily teach in English, which makes an immigrant’s transition easier than it might be from many other countries.

“(The) Philippines is a good country to look into particularly because the type of educational system they have in the Philippines is very much Westernized,” Garcia said.

Now, as the U.S. faces a national teacher shortage, school districts are looking at the Philippines once again. Garcia said it’s not surprising that the island nation is supplementing another U.S. workforce, largely for the same reasons as for nurses and other skilled professions.

“With the historical connection of the Philippines and the United States, and the educational system being very close to the United States, I think the Philippines is a natural choice for labor shortages,” he said.

Jobs in America tend to pay better, so many emigrate to send money to their families back home.

“The natural choice is to look for better opportunities for them – financial specifically – so that they can provide for their family back home in the Philippines,” Garcia said.