For years, a national database that tracks and maps landslides has had a major hole: Alaska.

That’s about to change. The state released a database this week that pinpoints where thousands of slides have happened in the past. The aim is to better understand the risk and prepare for the future.

It's a crucial tool that will help communities, researchers and government agencies “start extrapolating if there are certain slope angles with certain soil types or rock types that are more susceptible than others,” said Jillian Nicolazzo, a geologist with the state's Landslide Hazards Program.

Staff at the Alaska Department of Natural Resources created the inventory over the last three years by poring over more than 1,000 geologic reports, most of which date back to the 1950’s.

Those reports are from the state agency and the U.S. Geological Survey that were published while mapping parts of Alaska for reasons unrelated to landslides, like building roads or identifying mineral resources.

“If you want to know where to go mine a mineral, for instance, you need to know what the geology is, what kind of rocks might have that particular mineralogy that you're looking for,” Nicolazzo said.

The reports were largely created using aerial imagery, which means they also capture where landslides have occurred. Nicolazzo helped extract that information from each report, categorize every slide, and compile the data in one spot.

“It's a good step one, I think, to get it all in one place where it's easy to find. And then people can start getting creative,” she said.

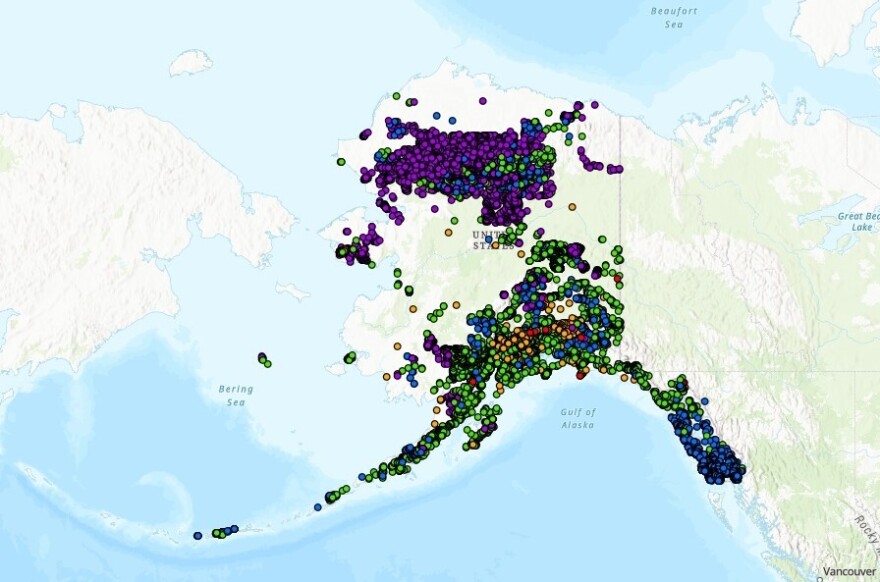

The new tool makes clear that Alaska is highly susceptible to landslides. It also highlights that certain types of landslides are more common in some areas than in others.

If you zoom in on Southeast Alaska, for instance, hundreds of blue dots appear throughout the region. They signify places where so-called debris flows have taken place. Meanwhile the Brooks Range, further north, is covered largely by pink dots. Those dots mark places where seasonal freeze-thaw cycles have triggered instability.

Something else that jumps out is that major swaths of the state at least appear to have no slides at all, including on the North Slope.

“It’s not that there aren't any up there. It's just that they haven't been mapped yet,” Nicollazo said, noting that the state will ideally fill those gaps as it continues to map new areas.

The new inventory will feed into a national one that the USGS built using information from states. That inventory does currently include some limited information about Alaska.

But the new data will “pretty substantially change the map of Alaska that they have on their nationwide map,” Nicolazzo said.