The teeth of Tyrannosaurus rex have been called "killer bananas," and a new study in the journal Scientific Reports shows just how hard those fearsome chompers could clamp down.

"What we came up with were bite forces of around 8,000 pounds," says Gregory Erickson of Florida State University. "That's like setting three small cars on top of the jaws of a T. rex — that's basically what was pushing down."

Erickson and his colleague Paul Gignac, of Oklahoma State University, initially looked at the bite forces produced by different crocodile species.

"Crocodiles are close relatives of dinosaurs," says Erickson. "It's probably our best model for looking at dinosaurs."

Their work involved lassoing, say, a 17-foot crocodile and getting it to bite on a glorified bathroom scale. "This is quite a spectacle, I call it 'bull-riding' for scientists," Erickson told NPR.

The researchers then took what they knew about crocodile jaw muscles and bite forces, and used that information to create detailed 3-D computer models that could reveal T. rex's chomping potential.

"T. rex was basically eclipsing the highest forces known for any living animal today," says Erickson.

He notes that the biggest living crocodiles currently hold the world record for measured bite forces, which his team found were about 3,700 pounds. Human bites come in at a paltry 200 pounds or so.

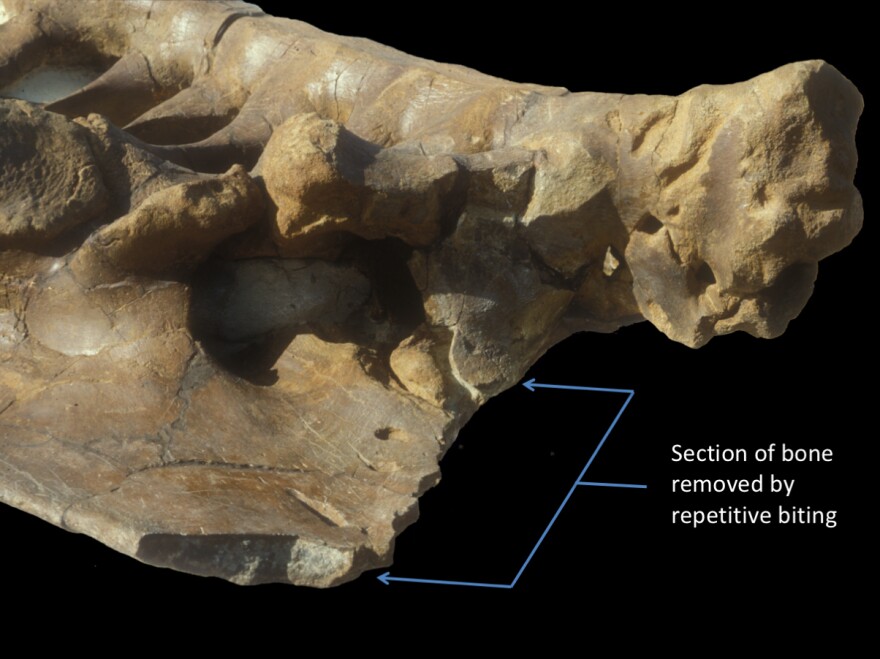

Unlike modern reptiles, T. rex could chew up enormous bones, to get the precious marrow within. That's thanks to the right combination of biting power plus blunt teeth that were serrated like steak knives, says Erickson. "It basically could slice through just about anything in its realm."

And it did — devouring everything from duck-billed dinosaurs to triceratops.

The researchers found that the tip of the dinosaur's teeth could exert pressures of 431,000 pounds per square inch.

François Therrien, a paleoecologist at the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Canada, says over the years there's been plenty of attempts to estimate the bite force of T. rex.

"Lots of those earlier bite force estimates were more theoretical constructs," he says. "They weren't really based or grounded in the modern world by comparison with some living animals for which we knew the bite force."

That's why Therrien likes this new analysis, since the researchers could calibrate their models with living crocodiles to see if they were on the right track.

"Overall, I think the results of that study are probably really close to reality," says Therrien, who was not on the research team.

"We feel very confident that the model is as accurate as can be made possible given the limitations of working with fossils," says Gignac.

If you wanted to rank the world's best biters in history, says Gignac, "T. rex would rank near the top but not at the top."

That honor would probably go to the largest crocodiles that ever existed, extinct beasts that were 35 or 40 feet long, he says. The researchers believe those could have had bite forces up around 18,000 pounds, over twice as high as what T. rex could do.

Copyright 2024 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.